G’day!

Welcome to Letters From the Road, and letter number 30. This one is coming to you on a Sunday night in Australia, which is the night every family has a roast for dinner, usually with potatoes and something green. Turns out, letters also go well with roasted meats.

For those of you for whom this is your first letter, welcome! Good on ya for reading. Letters From the Road is the story of a family road trip in Australia, told one weekly installment at a time featuring my journal entries written during the trip. The journal entries are word-for-word, and you’ll see them highlighted in the letter.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, but you want to get some letters coming to your postbox? One letter, one story, once a week. Too easy.

If you’ve just joined us and want to catch up, you can find the other 29 letters here, under the watchful eyes of Bill and Kermit.

Cheers,

Luke

Waking up to the rumble of a thousand road trains was not the most unpleasant way I’ve ever been pulled from sleep.

That would have been the time I was on a train bound for Turkey, and I opened my eyes to find men with machine guns standing outside the compartment and demanding to see my passport. But that’s a story for another letter.

At the time, though, the fleet of trucks at the Auski Roadhouse, seemingly all of them coming to life at once with a roar that built upon itself like a deep throated angry swarm of bees, seemed pretty high up on the list of unpleasant ways to wake up.

13 November 2019 - Karijini Eco Village

At 5 am, the engines started rumbling, the back up alarms beeping, and the mining people moved out. Like ants, the ants that have been working in our tent. By 8 am, they were gone, and we were left with the sound of trucks continually zooming by on the highway.

This rude awakening was the mediocre start to what would be a roller coaster day. Which in itself is nothing special, life is a series of ups and downs after all. But highs and lows were more common when living the life of vagabonds, forever moving from place to place. They were also more pronounced, the peaks and valleys coming at you fast, like waves on the beach. Part of this is because you have very few opportunities to retreat, to head to your corner, get some water splashed on your face, and your eye taped up before getting back into the ring.

You can find a place to put your chair so that no one else can see you, like behind a tree. You can spend an inordinate amount of time in the campground toilets, until you can stand the heat no longer and are forced to retreat. You sit in the cafeteria until the staff grows wary of your presence and you leave before feelings of guilt compel you to purchase something. You wander off to the other side of the campground for a spell. But ultimately you get on with what you had planned, even though you don’t want to and no one else really wants to either, because you’ve got no other choice.

Our day was a bit off kilter from the start, due to some well placed arguing at the end of the night. Then we had the opportunity for a good night’s sleep stolen from us by the mining trucks. Things did not pick up from there.

This morning Katie was blowing her nose - I’d like to believe she was blowing her nose and not picking it - and a fly came out. Oscar later emerged from the tent with bright green goo oozing from his ear.

Before that, I was sitting in my bed and heard Henry say, very nonchalantly, ‘Do you guys have any tissues?’ No, I said and I looked down to see him sitting hunched over, dripping blood into his hand. There was blood on his shorts, sleeping bag, and a swath on his pillow. It reminded me of the time my little brother Nick did the same thing at the house on Main Street where we grew up, except he didn’t catch the blood dripping from his nose, he let it drip all over my parent’s cream coloured carpet. I have no idea what black magic and industrial strength cleansers the carpet cleaners used to make the carpet right again.

Then later I found boogers in my eyebrow. Are these things, taken together, bad omens?

We’re in the Pilbara, Karijini NP. I pronounce it like it looks: Pill-bar-ah. At Kermits Pool, we met a park ranger who called it Pill-brah. I think he probably meant Pill-bra-ah, but it just came out Pill-brah. Then he went on to call it Bill. ‘I’ve been in ‘Bill for 2 years now’.

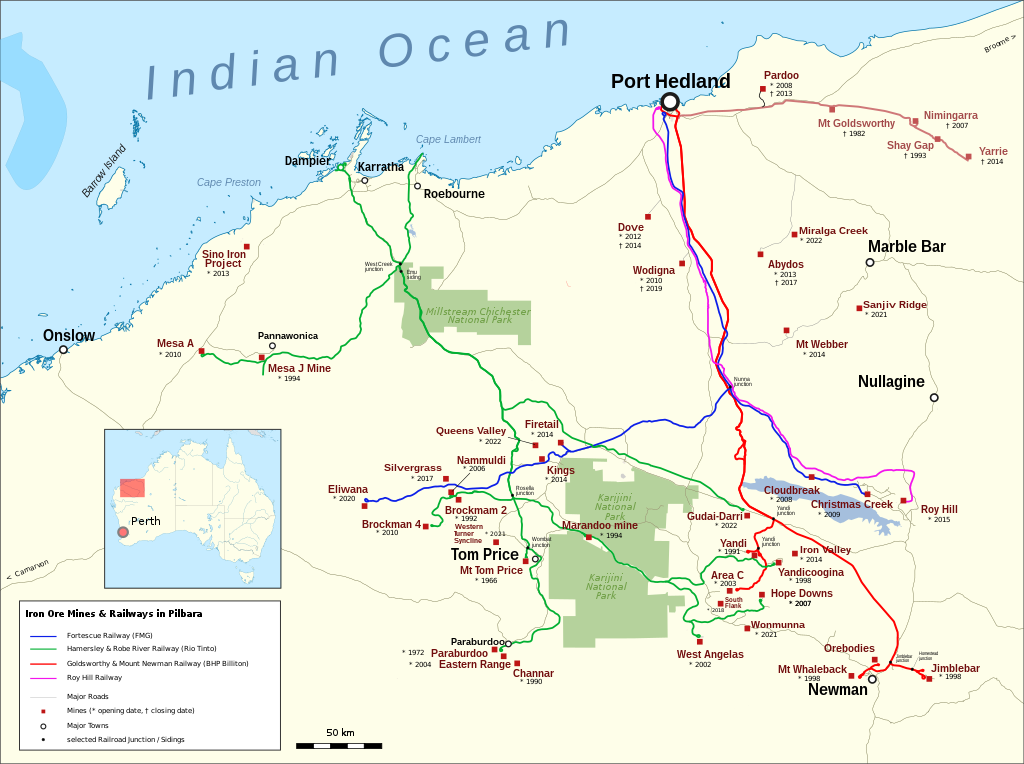

It’s a place that reminds me of some vast savannah, like something you’d see in Africa, with rolling hills, tan coloured spiky grass, and short trees that are scattered pleasantly around. Only the soil is the rusty brownish red that gives a hint of where you’re at, and what people do here. This is iron mining country, the heart of one of the most productive and prolific iron deposits in the world. On the wall in the Pardoo Roadhouse was a map showing resource projects in northwest Australia, and the Pilbara is full of iron deposits and mines, too many for me to have counted. And there was an Indian guy pulling $5.50 coffees off a proper machine, a not half bad brew.

I find the mines pretty fascinating, the infrastructure involved, the massive operations behind each one that are basically like building and running a small city. You generate your own power, you build roads and rail, you provide housing for your workers (which is partially due to the fact that mine sites tend to be in the middle of nowhere). They are considerable in scale, and there are lots of them out there.

At the roadhouse, I met an old guy who was out driving around the area by himself in a beat up van. He was very fond of the area, as he used to work in the mining industry, almost 50 years ago. He told me several stories about the good old days of the mines, how rough they were, a bit of danger being what you signed up for. Of the stories, the one thing that made my journal was something he said about the food.

Old German guy, been in Australia 48 years. In 1975, he was part of the exploration at West Angeles, a place that’s now a huge mine. He reminisced that anyone used to be able to go to mine camps and eat at the mess for $5 a meal, and the food was good!

If you remember my last letter, I wrote to you about the fact that Australia has the largest iron ore reserves of any country in the world. Our destination Karijini National Park lies within the Hamersley Range, easily the most impressive mountain range in Western Australia, as it is home to the 20 highest peaks in the state. The Hamersley is also home to 80% of the iron ore in Australia. You could possibly guess that there’s iron in them thar hills by staring out the car window as you’re driving through, as the land the deep brown-ish red colour that one associates with iron, a colour like the dried blood on Henry’s pillow. But 80% is outrageous - the amount of iron ore buried beneath the ground in the Hamersley Range alone is greater than the amount found in any other country in the world.

So what happens if that starts to go away? I don’t know how much of the iron ore actually gets sold to China, but I’m betting it is a majority. So what happens if China says... ‘we’re good at the moment, thanks!’. Or if they read The Art of the Deal and start negotiating prices, Trump style (which basically means telling Australia they need to accept next to nothing for their iron ore and if they say no they can get fucked, because ‘I’ll bet you know that China really doesn’t need your ore, China’s already got the best ore in the world. It’s huge. It’s fantastic.’)

What, then, happens to the red cities? All the ants? The armies of white Prados and their little orange bicycle trailer flags*?

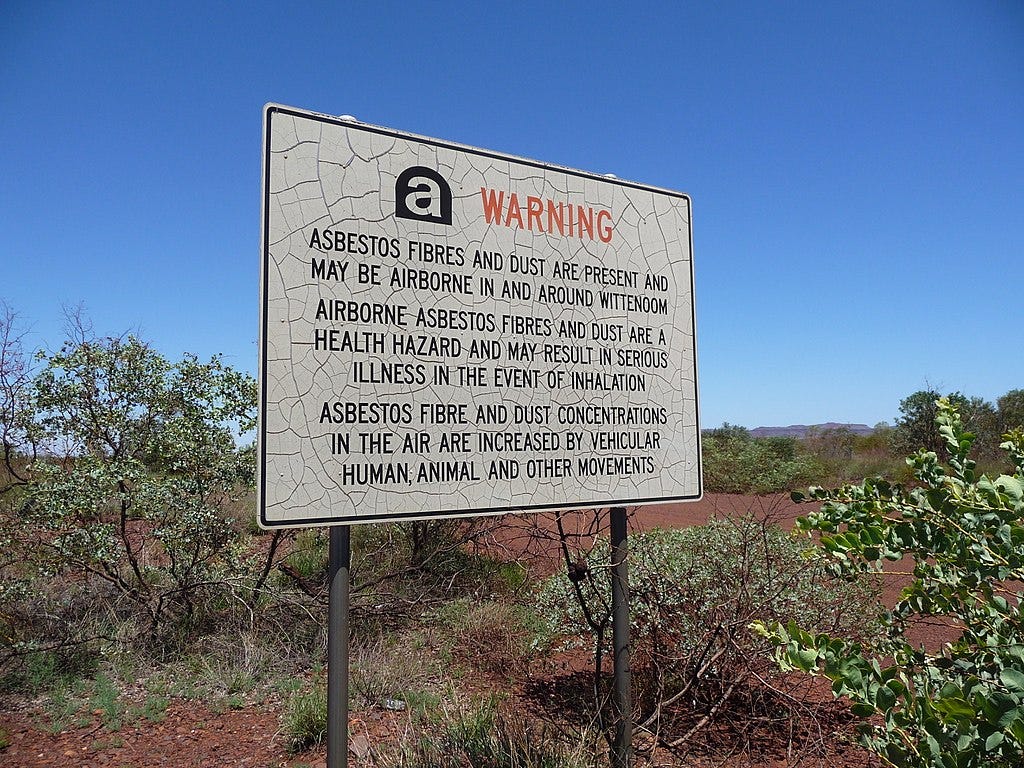

There is other stuff to be pulled out of the ground in the Hamersley Range in case that were to happen. You can find the usual suspects like gold, but the one I find most interesting is probably the most useless: blue asbestos. Not far from where we were staying in Karijini is a town called Wittenoom. Asbestos mining began there in the 1930’s, and it continued until 1966 when the mine closed, due mainly to the fact that it was no longer profitable, but also because people began to have concerns about their health. Residents remained in the little country town, trying their best to cater to tourists with a campground and some junk shops. The problems with asbestos had not gone away with the closure of the mine, though, and they’d not been forgotten either, providing inspiration for the 1990 song ‘Blue Sky Mine’ by Australian super group Midnight Oil.

Fast forward to 2006, and a government commissioned consultants report found that the danger to visitors due to asbestos in Wittenoom was ‘medium’, and danger to residents was ‘extreme’. I cannot guess what a medium risk of danger means, and I did not forfeit a few moments to read the report, but I’d say that the risk of doing anything in the Pilbara is medium, between the brown dust that sticks to everything within its reach, the insufferably hot temperatures, and the overpriced coffee. There’s nothing to question about an extreme risk, however. Based on the report, the government removed Wittenoom’s status as a town, and started the process of relocating residents. The last residents were evicted just last year, and Wittenoom is now a ghost town.

*Mine workers are indistinguishable from one another. All of them wear fluorescent high-visibility workwear and drive white Toyota Prados with little orange flags on the back. They made me think of the orange flag we used to have attached to a trailer Katie and I used to pull the boys behind our bikes. The purpose of our orange flag was to make the trailer more visible to cars, so they would catch a glimpse of it while they were scrolling Instagram, in time to swerve out of the way. I assume the miners used flags so the mining trucks, the behemoth ones the size of small buildings, would not smash them like little white ants.

After a middling morning, we drove from the Auski Roadhouse to Karijini National Park, and set up camp in a place called the Karijini Eco Village. The campground was almost completely empty, and they actually closed half of it because there was not enough demand to warrant keeping it open. It was inpexplicable, then, why they assigned us to what was possibly the most exposed site in the place, one only shaded by bushes and passing clouds. By the time we had gone through the motions of setting up camp, our motivation had melted.

Our original plan for the afternoon was to go to a place called Hancock Gorge, where a short walk led to a swimming hole. After setting up camp, however, our top option became sitting in opposite corners of the campground’s air conditioned cafeteria, however we knew inherently that the key to rising up out of the low points is to press on. And so we slid back into the car and headed for the gorge.

In the afternoon, we drug the boys to a place called Hancock Gorge. There was a walk, and Henry trudged along in front of us, earphones in and hearing nothing, Oscar walked at half speed because who knows why, probably because he was wilting in the heat. Katie and I were too, but we pulled it together to make something out of the day. In this weather, there is a strong compulsion to find a shady spot, or some aircon if you’re lucky, grab a chair, and sit for a spell. It needs to be a spell, not a few or a moment or something specific like an hour. You need a spell to allow however much time is necessary to mentally block out the heat before it steals your will and tomorrow’s energy.

The gorge walk was good, cool scenery where the layers of rock almost didn’t look or feel real. They were like fancy fake landscape versions of rocks. At the end was Kermit’s Pool, a gorgeous spot between high walls where the water is deep and cold. Both boys perked up by the end. Oscar did the most, because he swam.

To find a place like Kermit’s Pool in the depths of the dry and rocky Pilbara was remarkable, one of a series of places we would visit at Karijini that did not seem like they should exist, like little secrets that the world would reveal to you, but only if you passed a series of tests before you’d be allowed in. As I described in my journal, Kermit’s Pool was a little pool of deep, cool water, fed by a tiny waterfall. It was hemmed in on all sides and hidden from the world by the high walls of the red rocked gorge, some that jutted out and hung overhead. Unless you were there at a certain time of day when the sun was directly overhead, the light was almost always muted, which added to the sense of calm.

By pressing on despite all reasons that we should not, we’d been rewarded. Save for Henry, we all swam in the pool and left, refreshed.

As I wrote earlier, though, things change fast. By the end of the evening, we’d found a way to come back down again.

Henry acknowledged that Kermit’s Pool was ok, but then asked one of his loaded questions at dinner: ’Are we going hiking tomorrow?’ The only intent of such a question being having the chance to get a head start on whinging. In cases like these, I usually ignore the question.

Then he and Katie argued through dinner about the way Henry was eating. Too much like a savage, Katie told him. Doesn’t matter, Henry insisted, this is the way I eat, he says while stuffing half his serving of green beans in his mouth.

After getting nowhere, they switched instead to arguing about when, not if (they did argue the if, but the topic quickly shifted after Henry agreed to have a go at cleanup), Henry should clean the blood off his air mattress.

There’s blood on the air mattress, and the moms are circling.

We’re back next week with another letter, and more roller coasters.