The Australian Who Helped Save the Blues

The strange and wonderful connection between a bunch of Australians and a small town in Mississippi

In the northwest corner of Mississippi, deep in the American South, is a little town called Clarksdale. It’s just over an hours drive south from Memphis, 500 or so kilometres north of New Orleans, and close enough to the Mississippi River that you could sneak down every morning for a swim, if you wanted to.

Most people have never heard of it; most Americans couldn’t find it on a map. But if you pictured it, you might think of a place of cotton fields and the river, steamy summers, barbeque and the blues. The playwright Tennessee Williams set some of his most famous works in and around Clarksdale, like Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.

Something you don’t think of is Australia. You could argue that there’s hardly a place that’s further from Australia than Clarksdale, on all measures—culturally, historically, rhythmically, physically (obviously). And yet, if you were to go to Clarksdale, and find your way downtown to the corner of East 2nd Street and Yazoo, you’d see something surprising. Up on top of the old Bank of Clarksdale building, a big monolith made of white stone that has big columns next to solid front doors, is a flag pole. Flying there most days is the Australian flag.

It’s completely out of place, as if some Aussie backpacker strung it up late at night and no one noticed. But it’s no prank. The flag was put there as a symbol of the strange magnetic connection between Clarksdale and Australia—a connection best understood by talking about crossroads.

First, there’s a man named Robert Leroy Johnson. You may have heard of him. Legend has it that he met the devil at the crossroads of highways 49 and 61, and struck a deal to sell his soul in exchange for becoming the King of the Delta Blues.

And then there is an Australian named John Henshall. An economist and town planner from Melbourne, in 2001 John found himself at the crossroads of highways 61 and 278, just outside Clarksdale, faced with a decision: take a left to head for Clarksdale, or a right to go to Memphis.

“I’d been down to New Orleans to go to an American Planning Association Conference, and was driving back up Highway 61 to go to Memphis to get a flight back to L.A. and home. I had a guidebook, and it said that if you like blues music, you should go to Clarksdale,” John said.

He did not have to reckon with the devil, but John did have to make a spur of the moment decision, one that would take him off course and interrupt his return to Australia. The promise of blues music turned out to be enough.

“I am a blues fan,” John said. “And that’s why I turned left when I was going up Highway 61.”

John’s guidebook was spot on. Clarksdale is often referred to as 'The Birthplace of the Blues’, and the history of the music is thickly intertwined with the history of the town.

Clarksdale was founded as an agricultural community, initially for harvesting timber, then anything else that grew in the deep rich soil of the Mississippi Delta. Over time, cotton became king in the south, and so it was in Clarksdale. Cotton farming was labour intensive, and the hard work was done by black slaves at first, and then sharecroppers. Cotton was so profitable that the farms and plantations seemed to be forever in want of more people, and Clarksdale grew to accommodate the workers.

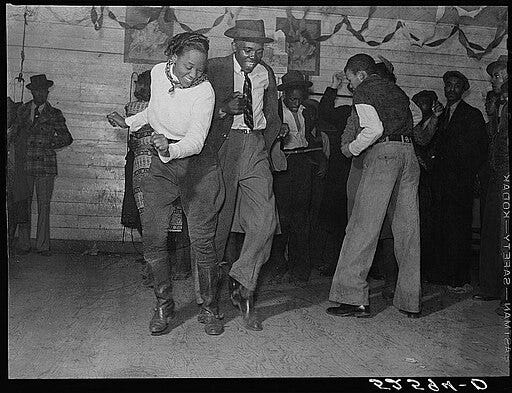

It was from the plantation workers that the blues emerged. The African American slave workers sang songs to pass the time in the fields that blended folklore and storytelling. In Clarksdale, the music grew organically as the town itself expanded. Over time, the music moved from the fields to the town, where it found a home on street corners and in juke joints—informal establishments for live music, drinking, and dancing that could pop up anywhere. Clarksdale, particularly its small downtown, became a magnet for the distinctive sound.

Starting in the early 1900s and continuing through the 1940s, many blues pioneers either hailed from or passed through Clarksdale at some point. You may not recognise their names, but like the blues itself, you’d recognise their sound. Ike Turner. Pinetop Perkins. Sonny Boy Williamson. Howlin’ Wolf.

In the 1940s, local radio station WROX employed its first black DJ, a man named Early Wright. Known as “The Soul Man,” Wright hosted a blues and gospel hour that amplified Clarksdale’s reputation as the epicentre of blues music and served as a launching pad for a new generation of musicians. Legend has it—Clarksdale is a place with many legends—that a young Elvis Presley would make the hour-and-a-half drive from Memphis, hoping to get on the air at WROX.

It was also around this time that Clarksdale’s decline began. Black slaves had been freed, but in the American South, “freedom” only went so far. Many newly freed blacks began leaving the South in search of better opportunities, heading north and west to build new lives. Blues musicians from Clarksdale were among them, seeking opportunities in cities like Chicago and Detroit. While this spread Clarksdale’s talent far and wide, solidifying the town’s reputation, it also meant that great blues music could now be found elsewhere.

Blues music is about longing and love. It’s also about hard times and loss, which is a fitting soundtrack for the Clarksdale that John discovered when he took that turn at the crossroads.

Finding many of the buildings derelict and boarded up, John wandered the cracked sidewalks of downtown Clarksdale like an explorer stumbling upon the remnants of a once great place.

"In the summer of 2000, you could have taken a shot with a deer rifle down Delta Avenue and not hit a car,” former Mayor Bill Luckett recalled about one of the main streets in downtown Clarksdale. "There wouldn't be a car parked there unless it was broken down.”

After its heyday in the 40s and 50s, the town had fallen on hard times. Cotton farms were no longer as profitable as they once were. Manufacturing had closed or moved away. Development had sprawled outward instead of focusing on the existing downtown—a trend common in the U.S. after World War II.

When Walmart set up on the outskirts of Clarksdale in 1971, it hammered a few more nails into downtown Clarksdale’s coffin. By the 1980s, the population was falling, the old WROX building sat vacant, and much of downtown was following suit. Social problems were rampant. Clarksdale, like many rural Southern towns, was sinking into poverty and fading into bland Walmart anonymity.

The blues music that John came to hear was fading.

Still, he was determined to give Clarksdale a fair go and stay for one night. Perhaps he was inspired by recent signs of life: a mural on the side of a building at the corner of Sunflower Avenue and East 2nd Street, depicting blues legends John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, and Bessie Smith, all of whom hailed from the Clarksdale area.

While John was wandering, a man called out to him.

“What are you doing here?” the man asked, a fair question in Clarksdale in those days. He introduced himself as Kinchen O’Keefe, better known as Bubba. He offered to show John around.

The O’Keefes were a part of Clarksdale’s history. Bubba’s grandparents had roots in the town, and his father served as mayor from 1949 to 1954, and these roots instilled in Bubba a deep sense of pride in the place. He understood what made the town unique, and had both experienced and heard the stories about Clarksdale’s heyday, when blues music could be heard on every street corner, and musicians were honoured as integral members of the community. They didn’t just perform in Clarksdale—they lived and worked there.

“Mississippi Fred McDowell,” a famous blues singer and guitarist, “used to pump gas for my father,” Bubba recalled.

Bubba had also witnessed Clarksdale’s decline. When his father was mayor, the population of Clarksdale and the surrounding county was around 50,000. By the late 1990s, it had dropped to 27,000. A trip to nearby Oxford, the nearby town that’s home to the University of Mississippi, brought Clarksdale’s struggles into sharper focus.

“The whole thing started after my wife and I had dined on the square in Oxford,” Bubba said. The Oxford Courthouse Square District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is a vibrant hub of bars, restaurants, and shops occupying restored buildings—the focal point of the community. When Bubba and his wife returned home to Clarksdale, they found their downtown dark and quiet. There were no people, no traffic, no signs of life.

“We had a vision of our town being a vibrant centre, where people can go eat, walk around, shop, and hear music.”

The stark contrast between Clarksdale and Oxford gave Bubba a renewed sense of purpose, and he got to work. In the late 1990s, he opened the Sunflower River Trading Company downtown to sell local crafts and music. He became involved in historic preservation and eventually began buying and redeveloping neglected properties, including the former home of WROX. Despite his efforts, when John arrived in town, Bubba seemed like one of a few sailors desperately bailing water from a slowly sinking Titanic.

An unlikely friendship blossomed from their chance meeting, and John’s one night in Clarksdale turned into three. There could hardly have been a more perfect person for John to encounter. Bubba didn’t just point out a mural painted on the side of the liquor store—he introduced John to the ghosts who once walked Clarksdale’s streets.

John was hooked, and the seeds of change were planted.

Eight years after his first visit, a town meeting was held in Clarksdale. Bubba and others had been gradually building momentum over the preceding years to reinvigorate the downtown area. However, city leaders recognised the need to organise their efforts and gain broader community support for these efforts to be successful. They needed a plan.

As it happened, John was back in Clarksdale on holiday and decided to attend the meeting. When the discussion turned to making plans, he raised his hand and volunteered to help. “That’s what I do for my day job,” he said.

The presence of a random Australian at a town hall meeting in Clarksdale didn’t seem to raise an eyebrow, but John was perfectly suited for the task. With over 20 years of experience in economic and urban planning and multiple degrees spanning commerce, social science, and the environment, he had a knack for connecting people and places. When he could get them working together, to really juke together, harmonising like a blues singers and a slide guitar, that’s what drove him. And his love of the blues made Clarksdale a perfect intersection of his passions.

John’s pro-bono offer was accepted, and he got to work.

Creating a vibrant downtown is like putting together a puzzle. There are the boring but important edge pieces that cover things like transportation, infrastructure, and zoning. In the middle you find tricky pieces related to economics and social challenges. And then there are the colourful pieces related to community and culture, and a few related to aesthetics—people like things that look good.

One other key piece, the lynchpin to the whole puzzle, is people. Clarksdale could plan all it wanted, but the town needed local champions to push for the changes, people who would be committed to lead the hard work on the ground. Three months later, when John finished his strategic plan to revitalise Clarksdale, he had given his old mate Bubba the lead role.

Another eight years had passed by the time I first met John at a party, a client appreciation event hosted by the economics and town planning firm where John was a principal.

It didn’t take long to realise this was no ordinarily bland client party. Out back, a guy was working a smoker, slinging southern-style ribs and pulled pork. The booze was good. And the music, I’m sure you can guess what was playing in the background. At the end of the night, I won the door prize—a multi-disc CD compilation of Delta Blues classics. It was a fantastic event but bewildering for an American transplant living in Melbourne. One minute I was stepping through a nondescript doorway on Pelham Street in Carlton, the next I felt like I’d shown up at a party in Memphis.

Curious, I invited John out for coffee, and this would be the first I’d heard of Clarksdale. Our chat stretched to several hours, such is John’s enthusiasm for the place.

“I didn’t know anything about Clarksdale before I went there,” he told me. “And I had no idea what would happen there after we made that plan. But I knew it would work…” he said with a smile.

I didn’t realise it at the time, but John was casting a spell on me when we were having coffee. It didn’t matter that he was talking about a town I’d never heard of in a state that’s impossible to spell unless you’re an American kid in third grade, and that the place was famous for people who lived there half a century ago and I’d mostly never heard of them either – John made it all sound like a secret spot where you could go to find a little magic.

I later found out that he’d been having similar discussions with a growing flock of his Australian friends and colleagues for years, and that we’d all been put under John’s spell.

One such convert was Adrian Kosky, a resident of a country town outside Melbourne. With John’s encouragement, Adrian first visited Clarksdale in 2006 and ended up buying a downtown building. After a renovation, he rented the ground floor to some Australians from Sydney, who opened a restaurant called Levon’s.

For his part, John is at a loss to explain the connection that he has forged between the two places. “I’ve probably got about 100 friends and family that have been to Clarksdale. And they all love to go there, and they go back a second time, and a third time.” he said. “Why it is, I don’t know.”

I didn’t know either, but three years after that coffee with John, I found myself on a road trip in the U.S. with my family. When I realised our route would take us through Mississippi, I knew we had to stop in Clarksdale.

I couldn’t help but think about shooting deer rifles down empty streets when we drove into downtown Clarksdale only to find almost everything closed. But in our case, we hadn’t come across the dying town that Bill Luckett had described, we’d come on a Sunday. Clarksdale may have changed, but Sunday morning in the South hadn’t.

Our first stop was to be the Delta Blues Museum, which is housed in the old Clarksdale train depot. But like everything else, it too was closed, so instead we criss-crossed the tidy downtown on the compact grid of streets situated between the Big Sunflower River on the west and the Mississippi Delta Railroad line to the south.

John’s plan emphasized ways to use history, culture, and the blues as a foundation for showcasing what’s special about Clarksdale, and evidence of this could be seen everywhere.

We passed a colourful mix of cafes, hotels, and gift shops, all occupying generally well-kept brick buildings that reflect the low-slung commercial style of the late 1800s. The single mural that John had come across on his first visit had spread—now, nearly every building on a corner featured murals commemorating local blues legends. The blues had returned to the street corners.

Of course there are several music venues. Chief amongst them is the Ground Zero Blues Club that’s co-owned by Morgan Freeman, who was born in nearby Memphis and spent part of his youth in Greenwood, Mississippi. Across the street is the Delta Blues Alley Cafe, and down the block, across the tracks, and caddy-corner from the local cemetery is the famous Red’s. You will not go wanting for live music in Clarksdale.

As we drove the quiet streets, I tried to imagine what they would be like during the annual Juke Joint Festival that is held each April. A celebration of music and food, it packs the downtown with several thousand locals and tourists from around the world. You’d have a hard time pushing your way through all the people swamping the streets, while the twang of a slide guitar or lonesome lyrics wafted out of one window or another.

We also noticed the tall blue markers of the Mississippi Blues Trail, a network of over 200 signposts across the state that honour blues legends and landmarks. These markers provide insight into Clarksdale’s history for pilgrims, much like Bubba had done for John years ago.

Downtown Clarksdale’s not perfect. There are one too many parking lots and enough ‘For Rent’ signs scattered around to catch your eye. But it’s easy to see what Bubba and John had envisioned all those years ago, a focal point for the community with plenty of reasons for people to come.

Before heading out of town, there was one last thing I wanted to see. I parked the car at the corner of East 2nd Street and Yazoo and stepped out to look across the street at a large white stone building. There on top, flapping in the Sunday morning breeze, was the curious and slightly magical sight of the Australian flag.

After standing at the crossroads and making his deal with the devil, Robert Johnson went on to become a blues legend. Despite recording only 29 songs and dying at the young age of 27, Bob Dylan, Led Zeppelin, and the Rolling Stones, among many others, all cite him as an influence. Among his songs was one called Cross Road Blues.

I went down to the crossroads, fell down on my knees. Asked the Lord above for mercy, ‘Save me if you please.’ - Robert Johnson, Cross Road Blues

After taking his turn at the crossroads, John was eventually given The Key to the City of Clarksdale for helping to revitalise the downtown. There’s also that flag flying from the bank building, hung there courtesy of Bubba, who is now the Director of Visit Clarksdale, the local tourism board.

Change happens slow in Clarksdale, but like the beat in an old Muddy Waters song, once things were put into motion they keep rolling along.

“Change takes time, and it seems that no one is in a hurry in Clarksdale. Each change, however slow, does add up and contribute, and over a number of years, that accumulation is quite noticeable,” Adrian Kosky told me.

John continues to return to Clarksdale every year, and each time he is surprised by something new.

During one of those trips, he came across a pizza place called The Stone Pony. It was packed. John tracked down the owner to have a chat with him. “This is a great idea, where did you get it from?” John asked him.

From the downtown revitalisation plan, the owner told him. The idea had been John’s. “I’d forgotten I’d even written that,” he said. At this memory he began to tear up. “You never know what impact you have on other people.”

John Henshall passed away recently at the age of 77. I’d like to thank him for the few hours that he spent with me in life, and also thank him in passing, as it encouraged me to dust off this old story that I first started writing in 2017, and to finally finish it properly.