G’day!

Welcome back to Letters From the Road, a collection of writing about adventures, journeys, and the surprising things you’ll see if you just do a bit of looking around.

Some adventures are massive ones, like the 2019 road trip I took with my family around Australia that encompassed over 60 letters. Some journeys are once in a lifetime (hopefully), like the evening I spent in the emergency department.

This letter will give you a bit of everything. It revisits a story that I wrote about an immigrant and his lasting impact on the Australian landscape, and the surprise that comes when that impact is found in the most unexpected places.

Goodonya!

Luke

In 1857, a 29-year old Englishman named John Danks boarded a boat to Australia. The 1800’s were a time of opportunity in Australia, and John was hoping to find his. Using the skills he learned apprenticing in his father’s metal factory, John started his own metal manufacturing business in the fast growing city of Melbourne. After a few years of establishing and growing the business, John was joined by his son Aaron, with the two operating under the name John Danks & Son.

The business grew to be quite successful operating out of Melbourne and eventually Sydney, making money selling agricultural supplies, tools, pumps, piping, and windmills with pastoral names like Billabong, Little Bill, and the Coo-ee.

John and Aaron also opened a hardware store at 391 Bourke Street in Melbourne where it was reported one could purchase anything ‘from a needle to an anchor’.

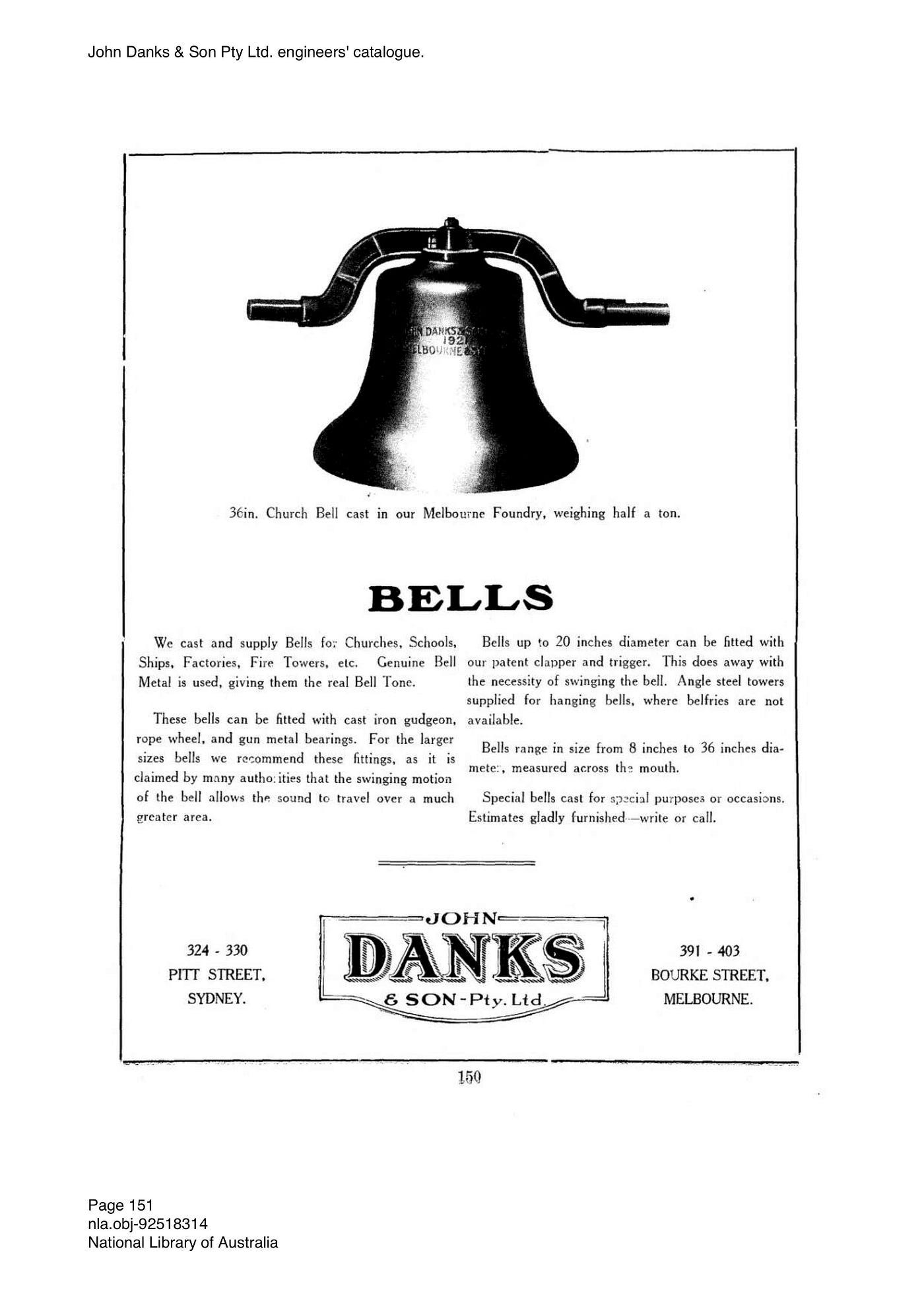

They also made bells. In 1925 they built a set of bells for a church in Mullewa, Western Australia, the first set ever made and tuned in Australia.

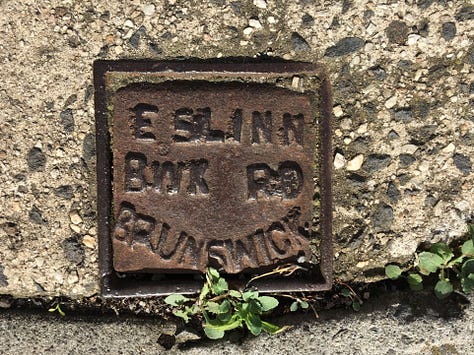

There is one thing John Danks & Son produced, however, that indelibly left their mark upon the city of Melbourne perhaps as much as any company, designer, architect or otherwise, before or since. It can be found all over the city, and if you’ve ever walked the streets of Melbourne, it is something you’ve probably come in contact with, yet never noticed.

Walking down the street is a frustrating endeavour in this day and age. One is forced to dodge and weave to avoid being run into by someone who’s walking with their head down, staring at their phone.

People have decided that using their eyes to watch where they are going when out walking around in public is overrated. Apparently the risk posed by running into stationary items, falling off kerbs, and avoiding buses, trams, and yours truly, is outweighed by the ability to fill every second of idle time with cat videos and a cesspool of emojis posing as speech.

Getting run into by distracted pedestrians is an annoyance, but it’s one that I’d like to encourage for the purposes of this story.

The next time you are out walking on the footpath, look down. Not at your phone, however. In this case, look down at the ground.

Keep your eyes open and before long and you’ll probably spot my new favourite thing that’s been hiding in plain sight, directly underfoot.

Hopefully you’ll then begin noticing them all over the place.

Behold: valve covers. Little trap doors into the underground world of water pipes, gas pipes and all sorts of other stuff. When a water line runs to your building, for example, there’s typically a valve cover somewhere around the perimeter of the building which conceals the switch which will turn off said water. Don’t get any ideas…

Valve covers are largely functional, with only three main requirements: First and foremost, conceal and protect the valve or pipe beneath. Secondly, don’t cause someone to trip and injure or make a fool of themselves when walking past. Finally, be durable. Outlast the footpath whenever possible.

What you’ll find, however, is that mundane functional valve covers can become interesting pieces of design in their own right.

They come in different sizes, shapes, and textures.

They portray history. You will not have to look too hard around Melbourne to find a cover adorned with the letters ‘MMBW’, a reference to the now-defunct Metro Melbourne Board of Works which used to manage the water and sewer for the entire city.

They also tell stories, like the story of the little metal manufacturing shop started by an immigrant named John Danks.

John Danks’ metal smithing made the Danks family wealthy, with both John and Aaron becoming prominent philanthropists of their time. Aaron donated some of that wealth to the church, who invested the money in a little plot of land east of the city centre, land which would later become the home of Epworth Hospital in Richmond. In 1925 Aaron was knighted for his good deeds.

Success for the Danks family extended beyond John and Aaron. John’s great grandson David Danks did not join the family business, instead he became a doctor. Pursuing an interest in the burgeoning field of genetics, he studied in London and at Johns Hopkins in the U.S. before returning to Australia. His research and efforts in founding the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute have led to him being called the father of clinical genetics in Australia.

The John Danks & Son’s hardware business lives on today, making up part of Home Timber and Hardware stores.

It also lives on, of course, through the valve covers which can be found dotted all over the streets of Melbourne.

Amongst the farm implements, knighthood, the church bells and the hospital, the most memorable, recognisable, and lasting remnants of one man’s journey from England to Australia are the little valve covers on the footpath. They tell the story of an immigrant seeking opportunity. Of windmills name Little Bill. Of knighthood, church bells and the father of Australian genetics.

And if you’re not looking down, you’ll probably miss them.

On the eastern end of the Nullarbor, the vast stretch of nearly featureless highway that runs for over 1,000 kilometres along Australia’s southern coast, is a town called Penong. Population 280, some of which it shares with a nearby smear called Bookabie, Penong is a dry and dusty town with a petrol station and a general store where the sign outside says “Last Shop for 1000km”. There’s very little reason to to stop for more than a few minutes, though, because this country is for driving: you’re either determined to push west deeper into the Nullarbor, or you’re trying to escape the Nullarbor’s barren treeless solitude and find civilisation. Penong just doesn’t give you the feeling that you’ve arrived yet.

We were escaping. It was late afternoon when we hit the edge of Penong, and my hope was that if we kept driving further east and got closer to the coast that we would escape the oppressive heat, which had pushed past 40C (104F), less than ideal when you will be spending the night in a big canvas tent.

I pumped diesel into the car, lost in the stupor of the heat and 400 kilometres of empty road. Looking around at nothing in particular, I noticed a sign pointing down a side road. “WINDMILL MUSEUM” it said. Diesel done and paid for, instead of getting back on the highway I followed the sign as if in a trance.

“Where are you going?” Katie asked.

“To the windmill museum,” I said. “We need a short break. Might be interesting?”

It didn’t take long before rising from the dust as if it were a mirage, appeared a shining metal forest. There were at least a dozen windmills in all shapes and sizes, including one that looked like a rocket engine.

Despite the heat, this sight was enough to pull the four of us out of the car to have a closer look. The windmills shone brightly in the powerful sun, some slowly rotating though most idle in the still of the afternoon.

While Katie and I went to walk amongst the towers, our boys Henry and Oscar were more interested in a contraption that combined a playground swing and a water pump. Swinging back and forth would make water come out of a spout. A sign on the pump said “Penong Wishing Well, Swing Pump, Another R&D Concept By Allan McColl”.

I like that it is another R&D concept by Allan McColl, which makes McColl - whoever he is - sound prolific. An unknown master, the Ben Franklin of the bush. It also made me wonder what other things Allan has been working on in his shed, hopefully more ingenious ways of tricking kids into working like maybe attaching a chain saw to a teeter totter, or a frozen margarita machine to a tricycle.

As I walked, I could see that each windmill had a name printed on its vane, a signature of the make or model. There were a couple Metters, one Southern Cross, and an enormous one called the Comet, the largest windmill in Australia according to a sign.

Past the Comet and off to one side was the smallest of the bunch. On the vane was the word ‘Danks’. It wasn’t Little Bill or the Coo-ee, this was the Danks Busy-B 5’.

It all came back to me upon seeing that Danks Busy-B 5’, the story of the immigrant John Danks and his son, the hardware store, the bells, and the valve covers. Even though I usually forget most of the things that I write, wiping the slate clean like an old frying pan before cooking the next meal, I’d never completely forgotten Danks, as I would still spot his work from time to time. But this was the first I’d seen that wasn’t in a footpath, and wasn’t in Melbourne.

“Hey look!” I yelled to Katie and the boys. “It’s a Danks windmill. You remember John Danks?” They looked at me blankly. “I wrote a story about him and all the valve covers in the footpaths.” This statement assumed that they had read my stories, and in particular one about things I liked that were found on the sidewalk.

“Is that why you have been taking pictures of all the things on the ground?” someone asked.

“Exactly!” I said with excitement. The boys kept swinging.

I scowled at them. This McColl guy and his R&D project had nothing on John Danks. Didn’t the boys realise that?

The weatherbeaten and rusty Busy-B stood there silently agreeing with me, a chain keeping the blades from spinning. It was an incapacitated relic, forever doomed to look upon the modern marvel swing pump working in the distance. I turned after a moment to walk across the dust to try the swing for myself.

It was surprisingly hard work, not as smooth as a regular swing because your motion had to crank the stubborn arm of the pump. Where swinging usually makes you feel as if you could fly, this was more like you were fighting to get off the ground. But it was strangely satisfying seeing the fruits of your labour flowing from the spout. And on this sweltering day, the water was cool and refreshing.

And then the heat caught up with us and it was time to leave. There was lots of road ahead. I doubted I would remember McColl, but I would remember John Danks and this chance encounter at the end of the Nullarbor. Gone again, but not forgotten.

I originally wrote the story about John Danks in 2018 and have since taken photos of metal sidewalk lids and manhole covers all over the world. I have published photo essays on lids found in Tokyo, Argentina, the Galápagos Islands, and New York City, and a couple more are in the works.